- Preventing the worst climate-change outcomes means using less fossil fuel

- Fossil fuels make us rich

- We don’t want to be less rich than we are

It arose from a short module I did here at the Faculty of Economics and Management at the Czech University of Life Sciences (Provozně ekonomická fakulta České zemědělské university), concerning energy economics.

The field is huge, and there’s no way to cover everything that should be covered in the time allotted, so I thought I’d lay a foundation by looking at big-picture connections between energy and the economy. Toward that end, I decided to milk two particular data sets and see how much insight I could squeeze out of them without any fancy techniques. The result is a series of data images that I think tell a story accessible to a broad audience, so I’m posting them here.

The energy data are from the 2017 edition of the Statistical Review of World Energy put out by British Petroleum. They supply data on the extraction and use of all the major and semi-major forms of energy, not for every country in the world, but for many of them (if your country is big and/or rich and/or produces a lot of oil, you’re likely to be in the dataset).

The economic data are from the Penn World Tables, an ongoing project that attempts to present basic economic data from every country in the world, in a way that is methodologically consistent across all countries, so that you can make meaningful comparisons among countries.

More information about the underlying data is in the accompanying post on data.

The first set of images is simply a comparison of GDP per capita and energy use per capita—in other words, we’re looking for a connection between the level of energy use and the level of economic activity.

In Figure 1, each dot is a country, and its position on the graph shows its GDP per capita (further to the right is richer) and its energy use per capita (further up is using more energy).

|

| Figure 1. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

The most obvious feature is that almost every country is bunched to the left, with wealth less than $50,000 per capita. The two exceptions are Qatar and—to an astonishing degree—United Arab Emirates. In other words, our outliers are two small states whose economy is founded on extracting and exporting oil.

Figure 2 does the same thing for 2014, and again we have a couple of outliers, with Qatar in the far upper right (very wealthy and using a lot of energy) and Trinidad & Tobago toward the upper left (not that wealthy, but using a lot of energy).

|

| Figure 2. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

This pattern repeats itself in intervening years, where outliers are very small countries, and/or economies based on oil exports.

Under those conditions, if we truncate our graphs to exclude the outliers, we will still be representing the great bulk of the economic activity in the dataset. And if we fix the axes to be consistent from year to year, it is possible to make meaningful visual comparisons among years.

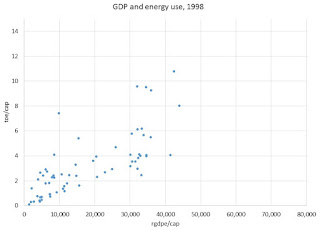

Following that logic, Figures 3 through 7 show 1970, 1980, 1990, 1998, and 2014, and each graph takes the horizontal axis only through $80,000 per capita, while the vertical axis is stopped at 15 toe per capita.

|

| Figure 3. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

|

| Figure 4. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

|

| Figure 5. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

|

| Figure 6. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

|

| Figure 7. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

Two things should be clear from this series. First, each year’s graph shows a strong trend upward and to the right: countries that are wealthier are also countries that use more energy.

Second, the clusters of points on the first four graphs have a roughly similar slope: the relationship between wealth and energy use does not change appreciably from 1970 to 1998. On the other hand, the points on the 2014 chart do seem to be “flatter”—as you move to the right, you don’t rise as quickly as in the earlier years.

This is shown more directly in Figure 8, which shows the data for 1970 and for 2014 in the same chart. There is significant overlap between the orange squares of 1970 and the blue dots of 2014, but the blue dots do in general fall along a flatter slope.

|

| Figure 8. Data from BP Statistical Review and Penn World Tables |

This flattening implies an improvement in energy efficiency.

In day-to-day life we think of energy efficiency as a sort of technological factor: a car is more energy efficient if it gets more miles per gallon (or uses fewer liters per 100 kilometers, as they express it in Canada).

But an economy is made up of such a myriad of different activities, that it would be difficult or impossible to compare the efficiency of economies on that kind of physical basis, and so what we use instead is energy used to produce a certain amount of GDP.

If two economies use the same amount of energy, but one of them has twice as much GDP, then that richer one is more efficient: it derives more wealth from a unit of energy, or it uses less energy to produce each unit of wealth.

Returning to Figures 3 through 7, a “flatter” scatter of points shows a relationship where countries are increasing their GDP without as large an increase in energy use as before, so the 2014 data in Figure 7 show economies that are, overall, more energy efficient than in the earlier years.

A later post will go further into this question of energy efficiency over time, but before that, the next one will address the issue of causality: Do rich countries use lots of energy because they can afford to (wealth à energy use)? Or are some countries rich because they use lots of energy (energy use à wealth)?

I’ll show a simple test that suggests that wealth derives from energy use (energy use à wealth), rather than the reverse.

(Next post)

No comments:

Post a Comment