A tangentially related concern is to get a 30,000-foot view of the financial system. Rather than losing my way in individual assets, is there some place where I can see the thing as a whole.

One place to get a sense of that is in what’s known as the “Flow of Funds” accounts prepared by the Federal Reserve.

Ideally, I’d like to get to a few different posts on this, but I’ll at least post this one.

The graph below shows the net worth of households and nonprofits in the U.S., from the beginning of 1952 through the third quarter of 2017 (as far as the data ran when I downloaded them a couple of weeks ago).

The green line on top is the value of assets (things people own).

The red line at the bottom is the value of liabilities (things people owe).

And the black line in the middle is net worth: assets minus liabilities.

All three lines are portrayed relative to potential GDP. For example, net worth in late 2017 is at a level of about 5 on the graph, which means it was five times as big as potential GDP.

It may be a spoiler to say that this post is about those peaks in the net worth line, in 2000, 2006-08, and now.

But to get to what I see in those peaks, I have to step back to the meanings of “wealth” and “net worth.”

At the individual level, the two terms can be synonymous, but when we scale up to the aggregate social level, they end up meaning different things, and that difference is the key to understanding why this graph troubles me.

Start with wealth. When we say that an individual is wealthy, we probably have one of two different meanings in mind.

One meaning is that their income is relatively high: year after year, the job they have or the company they own puts a large amount of money at their disposal.

The other meaning is based on what they have. Add up the value of any real estate they own, any bank accounts, any stock portfolios (plus other financial instruments—bonds, derivatives, futures, etc.). Then subtract what they owe: mortgage debt, credit card debt, other loans outstanding (student loans, car loans, etc.).

This person is an insignificantly small part of the market. If they wake up one day and decide to sell all their assets (house stocks, bonds, etc.), and pay off all their loans, they would be left with a sum of money that they could then spend on whatever they wanted.

That is the second meaning we might have in mind when we say an individual is wealthy.

It is also the definition of their net worth: add up the money value of what they own, and subtract the money value of their debts.

But this same conception can’t work for a whole society.

Start with the idea of wealth as meaning that you own many things of value. We’re not talking about one individual, insignificant in the larger scheme of the economy. We’re talking about the whole economy. If the whole economy wanted to sell all its houses, stocks, bonds, etc., to whom would it be selling them? It’s the whole society. And as for paying off its debts, to whom would it be paying them? Again, it’s the whole society.

So a society’s wealth can’t be understood as the monetary value of the things it owns, minus its debts.

Our other meaning of a “wealthy” individual—one who has a high income—does better when we scale it up to a whole society.

At least in theory, a person has a high income because the market has decided that they things they do are valuable—they have a high ability to produce valuable goods or services.

And that’s the same thing we mean when we say a society is wealthy: the society as a whole has a high ability to produce goods and services of value. They have a skilled workforce. They have an effective government that upholds the rule of law and provides needed public services. They have abundant physical capital (e.g., machinery, roads). They have useful technologies. And they have access to resources.

(Note that access to resources doesn’t mean that your country is itself rich in resources. It means you have them at home or can buy them from abroad at a reasonable price.)

There’s more of a discussion of GDP and potential GDP in the note at the end of this. If you don’t feel like reading that, the key takeaway is that potential GDP is a reasonable measure of our ability to produce goods and services that can be sold. In other words, it’s very close to the definition of society’s wealth.

The difference is that wealth covers the production of all things of value, whereas the GDP (or potential GDP) are focused on production of things that can be sold. This leaves out valuable things that can’t be sold, like clean air. (It may also include valueless things that can be sold, but that’s a more contentious point.) But that will turn out to be exactly the measure we want.

To see why, turn now to the issue of net worth on the scale of society as a whole: the monetary value of the things we own that can be sold, minus the value of our debts.

Parts of net worth are things that provide services to us when we own them, like our houses, or durable goods like our cars. But it’s also true that if you wanted to sell your house and buy something else (a piece of land, a boat, medical care), you could. Your house is both a place to live and (potentially) a claim on other things in the economy.

Looking at households and nonprofits, real estate and durable goods make up about 30% of assets in the U.S. The other 70% is financial assets. These are stocks, bonds, mutual funds, savings accounts, and the like. Unlike houses, they have no use in themselves. Their only function is that they can be sold to buy other things in the economy.

And this is where we bring the concepts of wealth and net worth back together. Wealth is your ability to produce stuff. GDP and potential GDP measure your ability to produce stuff that can be sold. Net worth is your pile of claims on stuff that can be sold.

With that in mind, it might be troubling that in the data available since 1952, the ratio of net worth to potential GDP is never less than 3. That is, our pile of claims on stuff that can be bought has always been at least 3 times as large as the amount of stuff we produce each year that can be bought. How can it make sense to have claims on more stuff than we can produce?

The key is that we never come close to everybody trying to sell all their stuff all at once. Some people are looking to sell part of their net worth (they’re heading into retirement, or their kid is heading off to college), while other people are looking to accumulate net worth (they’re preparing for retirement, or they have young kids and they’re saving for college expenses). So there’s a continual flow into and out of net worth positions. So it’s not inherently a problem to have more net worth than each year’s production of wealth.

At the same time, it makes sense that there is some limit to what is reasonable. Remember, other than houses and durable goods, the only point to owning assets is to sell them to buy produced things. If people have a larger pile of claims on produced things, at some point they’re going to try to use more of those claims than the economy can satisfy. As that reality starts to sink in, people realize that there are too many claims out there, and so assets lose value—the quantity of claims gets brought back down, closer to being in line with what the economy can actually provide.

That’s the lens through which I see this chart.

From the beginning of the data in 1952 into the mid-1990’s, the ratio of net worth to potential GDP fluctuated in a range from about 3.1 to about 3.75.

Then in from 1997 to mid-2000 it rose to an unprecedented 4.35, before it was brought to earth by the bursting of the tech-stock bubble.

By mid-2002 it was back down to 3.73, at the upper end of its “normal” range (or perhaps we could call it its “healthy” range). But then as the housing bubble started to inflate, the net-worth ratio started back up again.

It peaked in 2006 at 4.68, a new high, as the housing market peaked. It staggered sideways for the next year while the housing market sagged, before falling off a cliff at the end of 2007 as the housing market collapsed.

This time the bottom was all the way down at 3.6 at the beginning of 2009. And the consequences in the real world were the worst recession since the Great Depression,

Unemployment climbed to 10% and then took 7-and-a-half years to make its way slowly down to its low from before the recession.

Other useful measures of the labor market, like the participation rate and the employment-population ratio still haven’t recovered to their levels from before the crisis.

Millions of people lost their houses.

Millions of people experienced long-term unemployment, with average durations of unemployment hitting 40 weeks, while in a “typical” recession this measure only goes up to about 20 weeks.

The initial shock of the recession boosted Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign, as people were ready for a change.

The agonizingly slow and uneven recovery contributed to a social climate in which someone like Donald Trump had even a ghost of a chance. People were ready to just burn the place down.

And where are we now?

The ratio of net worth to potential GDP is a new record: 4.98.

Real-estate values have recovered to a point like in the early stages of last decade’s housing bubble, comfortably above any point in the last 65 years except the bubble itself.

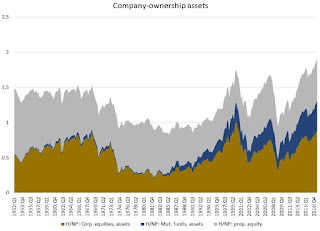

But the big driver is financial assets, in particular stocks, mutual funds, and proprietors’ equity in non-corporate businesses—in other words, the assets based on the value of owning companies, directly or indirectly.

|

| The gray on top is proprietors' equity in noncorporate businesses. The blue in the middle is mutual funds. The brownish color on the bottom is corporate stocks. |

Either the basic working of the economy has changed, and these new valuations are well-founded.

Or it hasn’t, and the current level of net worth is a warning sign, just like in 2000 and 2006, only bigger this time.

Note: GDP and potential GDP

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a flawed measure, particularly when we use it too clumsily as a proxy for a society’s level of well-being. But it is actually about the best possible measure of a society’s production of goods and services that can be bought and sold. This is also a pretty good stand-in for a society’s ability to produce goods and services that can be sold.

The potential GDP is conceptually simple: what level of GDP would you have if your economy had the “right” levels of unemployment and capital usage? That is, calculate the path of GDP without the ups and downs of the business cycle where sometimes you’re booming and sometimes you’re in recession. Defining the “right” levels of those things is inherently subjective, and getting from those “what ifs” to an estimate of GDP is inherently imperfect.

But both those steps are routinely done by various groups, including the Congressional Budget Office, whose numbers I’ve used here.

However imperfect the number is, it provides a sense of the development over time of the economy’s ability to produce, largely stripped of the perturbations from the business cycle.

Back

Thank you for the analysis. For the past year or so, I've been waiting for a number of people to wake up and realize "hey, most of the people in charge of the world's largest economy are fools!" This didn't happen in 2017, largely because there seemed to be sane people and policies left in place from the Obama years, and as we know, no one was able to make any big legislative moves until the very end of 2017. At that point, the U.S. decided that it really didn't care about tax revenues. And we've in early 2018 also decided that the government will spend with abandon.

ReplyDeleteSo now my feeling is that there's that "wake up" moment, coupled to the fact that (I don't think) you can as a government just go on borrowing and borrowing while cutting the tax rate. And here, they've cut not just the tax rate itself, but also cut most of the funding behind enforcing the existing tax rates, making it much easier for people to simply opt out with few consequences.

So... I don't know if you'd agree with the above analysis, although your blog-post makes me think you might. My question is, if we agree so far, what does the next phase look like? My guess is a fundamental realignment of both the US equity market AND the US currency. But I've been thinking something like that would happen for that last 30 years, so I'm hesitant to make any proclamations.

Nerd.

ReplyDeleteI have been married four 4years and on the fifth year of my marriage, another woman took my lover away from me and my husband left me and the kids and we have suffered for 2years. I met a post where this relationship doctor Robinsonbuckler11@Gmail.com have helped many couples get back together and i decided to give him a try to help me bring my Man back home and believe me! i sent my picture to him and that of my husband and after 48hours as he have told me, i saw a car drove into the house and behold it was my husband and he have come to me and the kids, he appologize to me and the kids and promised never to break up with me again. I am happy to let everyone in similar issue to contact this man and have your lover back to yourself.______________WOW!!!!!!!!!!!

ReplyDeleteThis is unbelievable... I love this!

Get back with Ex... Fix broken relationship/marriage..........

His result is 100% guaranteed.

He cures herpes with herbal mixture

-GENITAL AND ORAL HERPES

-HPV

-ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION

–HEPATITIS A,B AND C

-COLD SORE

-IMPOTENCE

-HYPERTENSION

-SHINGLES

-FIBROID

-BARENESS/INFERTILITY….

Patricia Bowen