This is a comfortable, modest square, with a yellow baroque church occupying a long corner of the space. I sat myself down on a park bench with the church to my right.

Opposite the church there was a pair of houses, mismatched in style, but both porticoed, in a way that suggested a small town rather than a provincial capital.

Across the square from me was an informal traffic hub, where taxis, horse-drawn taxis, and buses traded passengers.

A group of five boys are playing soccer on the square in front of the church—only one of the group had shoes on. The goal is the side of the steps that lead up to the church. There is a shot that gets way past the goalie and up onto the platform where a group of six elders is standing, talking, perhaps waiting for the church to open.

The ball hits one woman in the head. It doesn’t look like that hard a blow, but she’s dizzied and moves closer to the doorway to support herself. One of the boys comes up to apologize. The woman turns to scold him, but can’t persist long in the face of him taking responsibility for his action. She turns away and he reaches up to pat her head where she’s holding her hand, but he doesn’t quite touch her.

The square is pleasingly lived in. It’s not just the boys playing soccer, but many of the benches are occupied, and there’s frequent foot traffic through it.

The church bells ring—about a minute of rapid, high chimes, then one deep peal. About a minute after that, the doors open and the elders from the church porch enter. Most of the people who’ve been sitting on the benches eventually rise and make their way into the church as well.

The young soccer players have moved to a different part of the square as three older boys with a worse ball play directly in front of the steps.

A woman dressed for office work and holding a satchel and umbrella is sitting side-saddle on the back of a bike as her boyfriend/husband, dressed more casually, peddles her slowly away.

Now a different combination of five youngish boys is playing half-court soccer in front of the church: one goalie plus two pairs, each pair having a younger player and an older one. The ball gets away, and a 50-ish man jumps from his bench and fields it.

(You can see the church before the outside was fixed up here.)

After about 45 minutes of sitting on a bench at Parque Maceo, I make my way back toward Parque Serafín Sánchez, by a different street. The one I took on the way up was in remarkably good shape: façades well maintained, a look of modest prosperity. And it wasn’t because of tourist presence, as there’s no sign of tourist activity at all once you get north of Parque Serafín Sánchez.

The street I end up on to return toward our hotel is a different story. There’s a façade in front of a roofless shell of a house. On a corner, there’s a beautiful façade, well painted in a baroque pastel blue, but with decaying balconies. There’s a glimpse into a courtyard where there is, as the Czechs would say “bordel”—a big mess.

I also pass a grocery store that sells in “moneda nacional”, national money, the money that Cubans get paid in, and that foreigners aren’t supposed to have. In the warm climate the store is open to the street and I can see what’s in there, which is not much. Some sad vegetables, and a sparse selection of canned goods.

I’m tempted to go take a closer look, but I hold back. I don’t look Cuban; my Spanish is minimal; I’m carrying a backpack, which is not a common accessory in this country. I don’t want to be a voyeur: “My, what a quaint country you have. And such poverty. How charming!”

A similar reticence keeps my camera in my backpack. “Don't mind me. I'm just taking pictures of how your world is literally falling apart, and in two weeks I'll be on a plane back to a place that is somewhat better kept up, and that you can't visit. Thanks for the Kodak moment.”

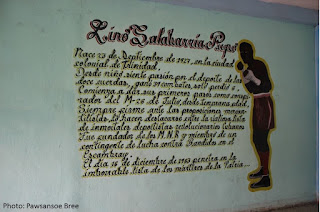

My stroll was the quiet, still center of the day, but the big event was a visit to Escuela de Iniciación Deportiva Lino Salabarría, which is a grade school specializing in sports.

We were ushered into the library, where a selection of the school’s students and teachers were waiting for us, with the principal etc. at a table up at the front of the room, along with Jesús there to translate.

|

| Jesús second from left. Photo: Pawsansoe Bree |

|

| Photo: Pawsansoe Bree |

They explained that the sports school was part of a larger system that incorporates physical activity broadly into civilian life.

|

| Photo: Pawsansoe Bree |

Physical education starts in daycare, and every caregiver also knows appropriate physical activity for the children in their charge. The attention to sports continues at every level. Each elementary school has a sport that it specializes in.

Every part of the country has a center for sports medicine, to support the activity of the athletes. And there are multiple school specializing in sports, like the one we were visiting (one in each province? I don’t remember, and my notes don’t say).

The students have regular classes in the morning, then work on their particular sport in the afternoon.

I asked about the reason for so much emphasis on the development of elite athletes through programs such as this school, and he didn’t really have an answer.

I had a couple candidate answers in the back of my mind, but I didn’t really expect to hear them. During the Cold War, athletic competitions became proxy venues for showing whether communism or capitalism was better, and my impression is that the communist side emphasized this more, particularly as they more visibly fell behind on the material comforts of everyday life. The Cuban attitude toward sports seemed to emerge from a time-warp with that spirit more or less intact.

On a related note, the approach to athletics had the aroma of the Soviet vision of the physical prowess of the whole population. They were building a “new Soviet man,” and just as his inner being would be rendered whole once liberated from the distortions of living under capitalism, so his physique would visibly reflect the healthiness of living under communism. The sports schools were building up a cadre of people who fit that image.

On the street, however, the average Cuban doesn’t particularly live up to the ideal. There’s less obesity than in the U.S., though that’s hardly a surprise in a country with less food and, of necessity, a less sedentary habit.

So I don’t know why the country puts so much effort into sports, but I can think of a good reason which the people at the school didn’t mention: as long as the students are getting a good regular education as well, there’s a lot to be said for helping them to excel in something, anything.

After our formal session in the library, we perused the materials on the walls, there to remind students of the glories of the revolutionary struggle and its heroes.

|

| Che: Forger of the future |

|

| Hartwick student loving some revolutionary reading material |

|

| Our group. The six people on the left are teachers and administrators from the sports school. |

|

| The principal lining up his students to pose with us |

|

| I like the movement in this shot as the Cuban students continue on their way to classes |

Some of us were also intrigued by the equipment in the room, which seemed relatively basic.

We saw volleyball practice—including a young man with an incredible jump serve—martial arts, wrestling, and swimming.

|

| They seemed to be practicing water polo in a nearly-empty pool |

|

| Photo: Pawsansoe Bree |

|

| Photo: Pawsansoe Bree |

After we got caught in a rain squall, we were invited back into the library to enjoy a snack of fresh fruit: pineapple, guava, and papaya.

Among the things that caught my attention in the discussion at the school was the refrain about “putting the human in the center of our consideration.” It was the same thing we’d heard in Cienfuegos from the jurists and from the doctors at the medical college. When you hear so frequently in such varied settings, it takes on the feeling of a party line. It may also be an admirable ideal toward which some people honestly strive, even if the country’s system limits the ability to do that in the political sphere, while attempting to enable it in other areas.

After the school we found ourselves lunch, stopped in at ICAP (the Cuban Institute for Friendship Among Peoples), which is housed in a beautiful old house of a wealthy citizen from colonial times, then wandered on our own.

|

| Inside the local headquarters of ICAP |

The bullet points at the bottom of the sign give more detail about the workings of the dual currency system:

- National currency is accepted at the exchange rate determined by CADECA [the official state currency-exchange booths]

- Payment in CUP is accepted in all denominations of that currency [that’s a nice gesture]

- For a single purchase you can combine partial payment in both currencies and in electronic cards

- Change is given in CUC

- [I think the last bullet means that if there’s a currency devaluation, the price in CUC will be changed to reflect the new realities]

After a little shopping, I wandered with some students back toward the main square and into the local branch of the National Library. The space inside is stylistically closer to the main building of the New York Public Library than to your random place for checking out books. There’s the obligatory bust of José Martí,

an elegant dome resting on Corinthian columns,

and a double staircase rising underneath the dome, leading to a platform for students to pose on.

A student wandered among the shelves and was informed that this is not an open-stacks library. You look up what you want, and a librarian goes and gets it for you.

The upstairs reading room leads to a balcony overlooking the main square,

with a view off the side (southward) to the Iglesia Parroquial Mayor del Espíritu Santo, with its strikingly blue tower.

There was also some first-class electrical work.

From the library, I walked with two students down the street to the church with the blue tower, where we ran into Pat and some of the other students. For a CUC, you could climb the tower, which was worth it. The view was reminiscent of Trinidad, out over rooftops to distant hills (a little more distant than from the tower in Trinidad).

Another part of the experience was that the staircase required a small dose of faith to keep you climbing. And once you got one level below the top, you could see the clock mechanism, with the shafts coming out to clock faces on the north and south sides.

“What’s this wire coming up from the mechanism?” a student asked.

“I’d guess it pulls the hammer on one of the bells up top.” So when we got to the top and it was coming up on 3:00pm, we decided to wait to see the mechanism work.

|

| Students waiting to be deafened by a bell |

3:00 came and went—no bell. I went down a level to look at the clock face. “Oh, it doesn’t say 3:00 yet.” Then it did—no bell. So we gave up and were just heading down past the clock faces when we heard the bell mechanism whir to life. The students dashed back up, but not quite in time to see the bell hammer move.

In the afternoon I tried my luck at the games arcade and internet room just up the street from the hotel. It turns out that Gmail is blocked in Cuba (as it is in North Korea, Iran, and, I think, Syria, if I correctly remember the message that came up). Verizon, however, let me in, so I went into Kate’s email and sent her a message. But it had to be brief, since the connection I had was extremely slow.

As with the night before, dinner is up the street at the Plaza Hotel. While we’re waiting to be seated in the hotel’s dining room, Jesús introduces us to a fellow guide, who turns out to be leading a delegation from Food First.

This is an American group co-founded by Frances Moore Lappé, famous in the food world as the author of Diet for a small planet. Their goal is to end hunger through ending injustice in wealth distribution and land holding, and they support small-scale farming using environmentally sustainable practices.

Due to a peculiar twist of history, Cuba is a natural place for a Food First delegation to visit.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba was suddenly thrust into a desperate situation. An important part of how their economy worked was that they sold sugar to the Soviet bloc for more than the global market price, and the Soviets sold them oil for less than the market price. The overall effect was a Soviet subsidy to the Cuban economy that accounted for a quarter of its economy.

This subsidy allowed Cuba to import modern agricultural equipment and the fertilizer and pesticides those machines would apply—and of course it directly provided the fuel for them to run.

With the collapse of the Soviet bloc and then the Soviet Union itself, all that went away. In the absence of the inputs for conventional modern farming, Cuba was forced to adopt a makeshift organic agriculture. It came to be held up as an example of how other societies might respond to a sustained global downturn in oil production (the phenomenon known as “peak oil”), but also as a country with unusually widespread use of organic practices.

About 10 years ago, when I was on the board of the Center for Agricultural Development and Entrepreneurship here in Otsego County, our executive director and another board member toured Cuba to learn about their approach to farming. So I was naturally curious to talk with this Food First delegation that happened to be sharing our dining room.

They’re in the country for nine nights, seeing lots of farms, including in the Viñales valley out west, where we’re headed in a week.

One member of the group was particularly skeptical about what they were seeing and being told, though she was merely sharper in her statements than were her companions, who generally shared her view that the country’s farming isn’t as organic as it’s portrayed. “And besides, most of the country’s food is imported.”

(I later took a look in the Food Balance Sheets from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Cuba is almost entirely self-sufficient in produce, and they produce most of their own potatoes, and they raise most of their own pigs, and almost all their own cows. But they are largely dependent on imports for corn and chicken, and entirely for wheat, which goes to staple bread, and also for soy, which makes soybean oil, which in turn provides 168 calories per capita per day, an important source of fat in the Cuban diet.)

Potatoes were a particular bone of contention. Jesús had told us that potatoes can’t be grown organically here, because the climate is too different from the plant’s original home in the Andes. But a member of the delegation is under the impression that what’s needed is a change of mentality in order to adopt the practices that would work here.

Much as I was starting to feel that “putting the human being at the center” was as much as anything a slogan, Ms. Skeptical had a sense of there being a party line regarding Cuban agriculture being so organic. And along with the party line, there were things that were being left unsaid. I guess that’s the natural counterpart to the existence of a party line.

|

| The blue tower, viewed down a pedestrian street near our hotel |

I am so enjoying these. Related: http://99percentinvisible.org/episode/viva-la-arquitectura/

ReplyDeleteThanks for the link. We didn't get out to ISA, but will try to put it on our itinerary for 2017.

Delete